Babies in the womb may see more than we thought

By Eric Craypo

Article written by Robert Sanders, UC Berkeley Media Relations

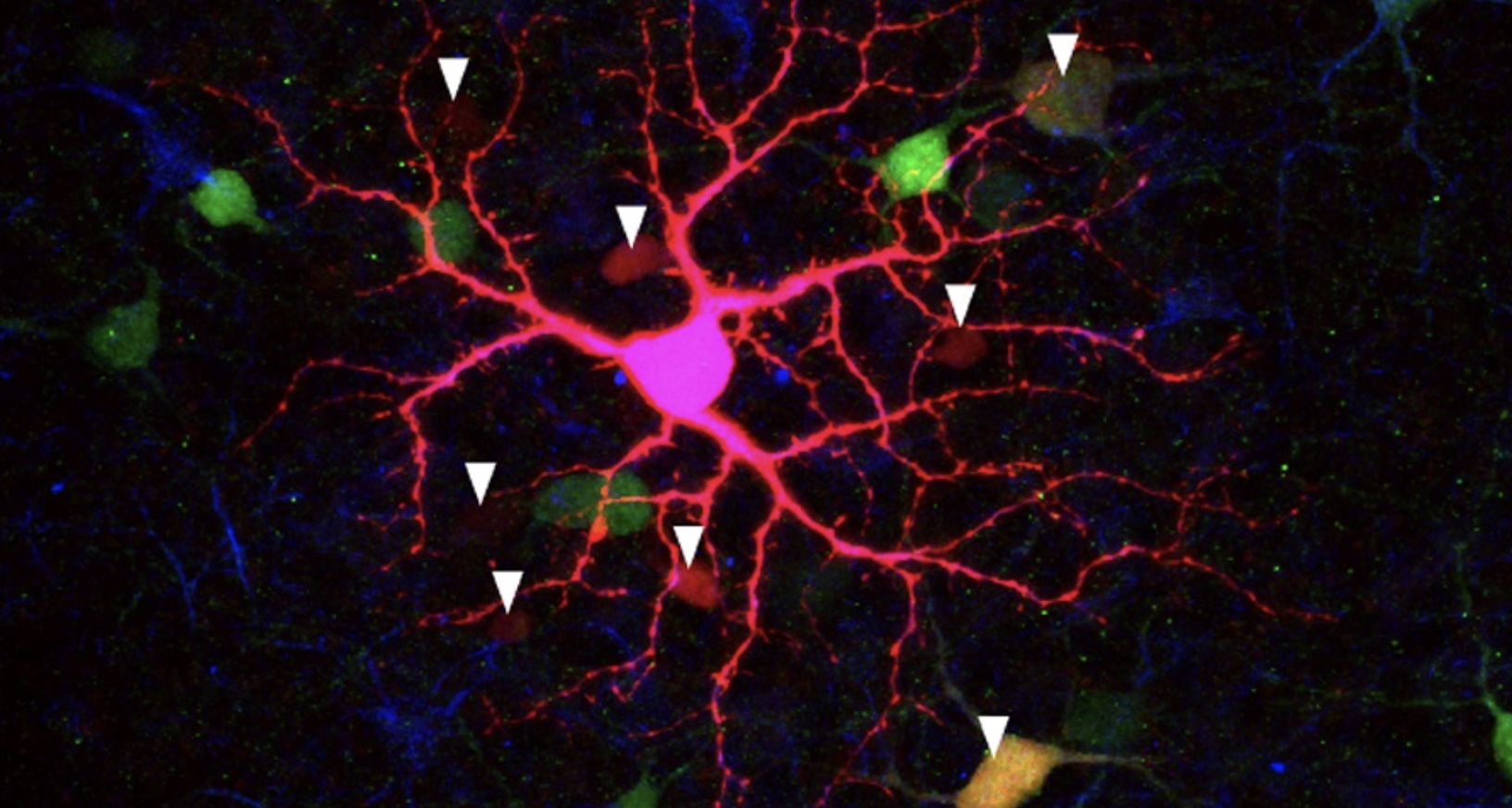

About the Image

By the second trimester, long before a baby’s eyes can see images, they can detect light.

But the light-sensitive cells in the developing retina — the thin sheet of brain-like tissue at the back of the eye — were thought to be simple on-off switches, presumably there to set up the 24-hour, day-night rhythms parents hope their baby will follow.

University of California, Berkeley, scientists have now found evidence that these simple cells actually talk to one another as part of an interconnected network that gives the retina more light sensitivity than once thought, and that may enhance the influence of light on behavior and brain development in unsuspected ways.

Marla Feller, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology, and a member of Berkeley Optometry's Vision Science Group, is the senior author of the paper, which appears this month in the journal Current Biology.

Read More